One

The violin is in your hands, pale as the tao we shared, stuck to the soles of our teeth

It is at your side, with the shiny brown varnish, the moment we share: surreal

Like the one picnic, red and white cloth between our legs, day cotton. golden sunshine streaked

on cheeks flush with first love’s embarrassment and shine like your music

Except our cheeks are white now, Snow White’s dove circling

As I watch you from the third seat on the left 50 feet above the life stage

a forgotten shadow

A stranger once again, like two years ago

Two

You start singing with your bow, the black air pooling and stuffy,

spotlight on your freckles, tiny stars painted on the sky that is your face, tanned

I remember. You have 7 freckles, three on your hooked nose, Imperfectly flawless

The notes on the page floating off in your fervor and concentrated effort

Three

The music starts slow and cautious, the space between your body and my flowered bosom

Your eyes mixed with dusk and honey, the dawn of something new: perhaps

You smiled, a sideways C, flattened, even when I put on shades, my mask in tints

But you peeled off the pain and anguish floating to the surface, vulnerable

You were connected to me in thick strands and blood

Perhaps I should’ve disappeared, my weight crushing your will to live weightless

Even when I screamed in the war for redemption, numbness spreading in the blotched lake

Your index finger digs into the string born, Dark and dissonant chords ascending upwards as if there is no time left to waste

You stayed, hugging me close, a bear hug on my torso’s curve

Even when I thought my arms too thick

My skin too pale and oily

And my hair not straight enough like the pretty ones

Feeling returned to my body, yours

Mind stronger than will

Shielding me from the wailing gale on our house, intruders

From the bottomless abyss so carefully chosen lest I slip

That fragment my mind into pieces you sewed together

Again and again

Four

You play the fourth movement, the mist and uncertainty fading with new phrases

Reaching the climax of our story, my head resting on your beating chest

The melody tugging at the fated strings that ties the mask to the melted face

This is the piece that we call ours, our relationship’s course in an arch

And paper thrown

Sitting on the long piano seat, the keys gleaming with promise, salty perspiration mixed with dry paint

Not marred with me hurting you, love our white lie, teeth out

My secret in your electric gaze on mine, straining for truth in the lie

Of course I’ll never kiss and tell, watching you now, my throat condensing in waves

Crescendos and fortes outlined on the faded linen sheets,

The energy rising and falling with moving notes gliding across silver strings

Rough and shallow, destined to flow and run out,

And move us in the moment of passion we call lover’s curse

Yet we persevered, a foolish youth’s dream

It was an illusion in the heat

Finale

Every piece has a beginning, middle, and end I think

Your hand catching the stream of tears from my eyes,

Free and drowned

There is silence in tone, a space where I once fit perfectly

And when you bow, a tear trickles down your frosted cheek that I once kissed

Alas I had long left the auditorium and your heart in between the notes and bars

Behind your smooth mask of apathy, fist in heart

You smile and it’s done, as fast as it started like the end of a movement

The end of us, the word sounds weird and

We are strangers once again

Passing shadows in the moonlight as our witness

The symphony ends, the moment gone with the spotlight

Jacqueline Wu is a writer from Long Island, New York. She is a contributor and editor of the acclaimed magazine, Cinnabar. She has also won several art/writing competitions, previously recognized by the Scholastic Art and Writing Awards. She is forthcoming in Body without Organs and Remington Review, among other publications, and she hopes to be able to continue to inspire through her work.

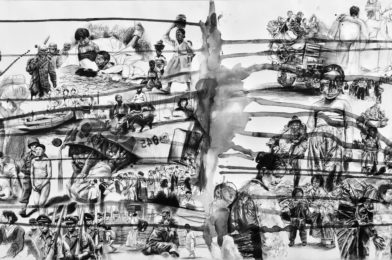

Visual Art By: Ayala Cris