The rattle of an aging radio agonizing over war and the address of his childhood home are faded structural realities. He grew up in isolation with an erased memory after contracting encephalitis, and he also grew up embraced by a loving family. He had nothing or he had everything. It depends on which way you want to tell it.

From his pipe, wispy gray strands of smoke swayed like living ghosts. Sunshine shimmered through his dusty window shades onto strewn book stacks and his silver threaded hair. Now with the wind exhaling, drifting the smell of fish from the bay into the walls of my grandpa’s apartment, he sat alone once again—this time in the vortex of the COVID-19 crisis.

When time slowed to a tormenting crawl, he turned on CNN. The news led him through the possibility of death and despair, a borderless sphere where loneliness reigns and hope is an ancient entity. With the click of the off button, he entered into a state of pure illusion, a state of numbness, like the numbness that follows an injury, before pain starts to make its way through. Everything seemed less real under the waves of oblivion, and that’s what he needed. I knew he longed for fiction.

Like the planets in celestial orbit, he was distant and lying beyond reach. Growing up in an era where silencing pain was status quo, Poppy maintained an emotional shield against vulnerability. To bridge the generational gaps between us, I searched the apartment for remnants of his former life. I found a 1960s Diana Camera wedged between tattered baseball cards and faded news clippings.

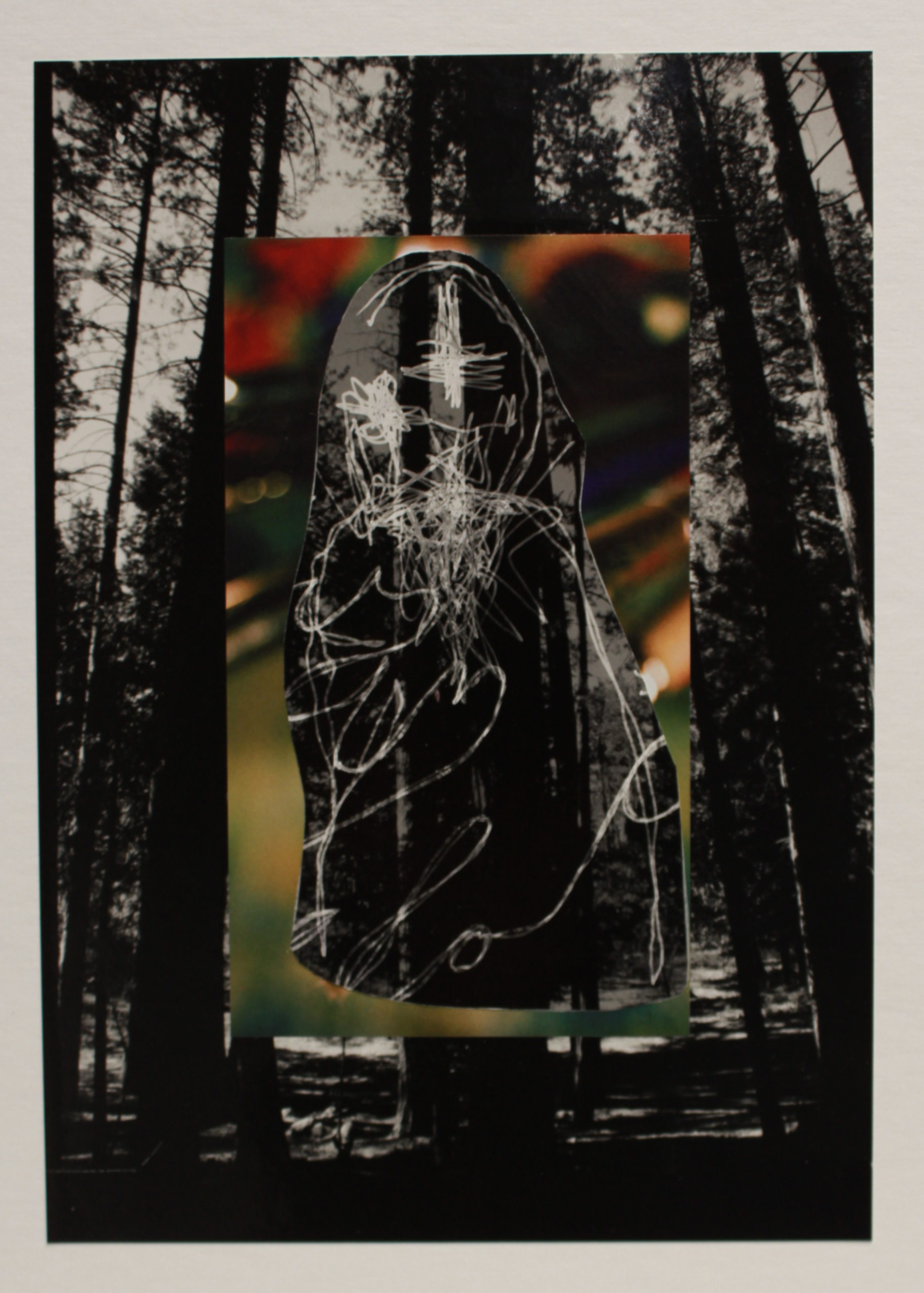

This unassuming blue and black piece of plastic was embedded with supernatural sorcery. With its transcendent powers, Diana dismantled Poppy’s manufactured illusion and revealed the true emotions beneath his facade. I photographed the lines of solitude etched in his forehead, the deep ravines of shadows that shrouded his existence. Through the lens of this vintage telescope, he communicated his untold stories and sorrows from youth: bursts of uncontrolled electrical activity between brain cells and his body bound to the wheelchair he called home. Emotional transparency, once an elusive concept, became a source of healing.

In my garage, aka the makeshift darkroom, I began to develop this picture while listening to Stevie Wonder’s “Love’s In Need of Love” melting on the record player’s rusting needle. In tune with his melody, it occurred to me that this fragmentary image allows me to peer into the larger questions of the moment, into a country mourning the loss of human connection. The pandemic has been an exercise in subtraction. Poppy has experienced the voids left by neighbors who have succumbed to COVID-19 and the absence of friends and family. And then there are the intimate things that are gone: the handshakes, pats, and the strokes that warm daily interactions.

As the photograph dried and the gradients of grey took form, I analyzed Poppy. In his chair surrounded by tchotchkes, he stared at the pictures of his former dog and my Grandma in the 80s with cheekbones adorned in bubble gum pink rouge at the roller skating rink. When days meld into one and the pipe’s vapors envelope his being, he entered into a permanent haze of oblivion to escape living in a constant flashback. His current existence cloistered in his apartment is reminiscent of his childhood when his fever rose and was forced to stay in isolation to recover. The black and white film replicated his portal to the past. Somewhere at the intersection of peace and longing, his concealed pain thawed within the picture.

I picked up Poppy the day I finished processing the film, and we went to the deli on Cross Bay Boulevard. I had not seen him for a long time and his sullen face slowly waned. It was early in the morning and for a fleeting moment the chaos of the pandemic blurred into stillness. We ate our bagels and lox together by the bay, the salty threads of air whispered and the ebb and flow of waves hummed. In between coffee sips, we talked about our shared feelings of loneliness and yearning for normalcy. I finally knew what was beneath his kaleidoscope eyes, once a confusing mosaic of opaque colors. Now, a translucent vision of an old man trying to nourish his relationship with his granddaughter and cope with childhood trauma.

When Gabrielle Beck is not writing or photographing, she can be found repurposing vintage denim. She is a finalist for New York Times “Coming of Age in 2020: A Special Multimedia Contest for Teenagers,” and recognized by the National Council of Teacher’s of English.

Art by Sarah Little