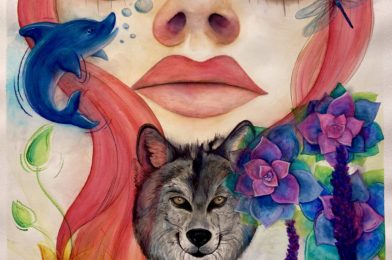

There she was, clutching a pair of buttocks – that is, her painting of buttocks, and giggling with the fervor of one having deliberately defied some code of acceptable behavior. In that kiosk aching with smoke, the ad appeared to me in a kind of divine light, sudden and piercing. Yet it was not her girlish laugh or the choice of subject which piqued my interest. It was the incredible perfection of the buttocks themselves. At the first widening of the hips, a pattern of violet bougainvillea broke up the skin in a daring, spring fashion, while an anonymous back sunk into a void of dark sun. In fact, the painting was the furthest thing from crude: it epitomized the Platonic gene which, as I would discover, permeated through all her work. She had achieved in rendering buttocks noble. It was at that moment, in the fast–approaching night, that my eleven–year–old self decided to start painting lessons.

The Doors, 1996, latex paint on wall

The studio was uncomfortably close to the tracks. Pulling up in the car that first day, all I could register was the metallic ring of a train being roped towards some violent place in the direction of Lausanne. As it departed, I myself began to drift towards a bleached structure, clinging all the while to my mother’s open palm, and more than a little white. Overhead and unnoticed by me at the time, there was a sign (Le P’tit Pinceau) pinned to the concrete like a forgotten doll. This was the place.

Sketch 1 of 4, 2052, blue pencil

In 1903, Rainer Maria Rilke wrote, “more unsayable than all other things are works of art, those mysterious existences, whose life endures beside our own small, transitory life.” I have trouble with this. After all, even art, our most desperate attempt at penetrating reality, is inevitably eroded, morphed, and mistranslated. Our souls become misshapen; our eyes witness the appearance of the ugly trace of time, la maladie ultime. Only to the artist himself can the work appear transcendent. And although their truth may continue to live inside it, it will be invisible to all others.

Red Scale, 1996, acrylic on canvas

The teacher introduced herself as Mirabelle. I learned her surname only later, from her paintings, signed M. Desrosiers. And truly, the person was as vivid as the name: she was short and red, as if her small body would not always be able to contain its share of blood, and one day she would burst, fountain–like and magnificent, onto one of her canvases. I had just met the creator of The Buttocks, a living descendant of Circe’s. It was the beginning of my hopeful conversion to the art world.

I was quickly disillusioned when the sorceress laughed at my idea of a painting (an owl swooping onto an invisible subject) and led me to a carboard box brimming with prints of popular internet searches. Above this first floor – muddied by the latest tornado of paint – there was a second consisting entirely of a narrow, indoor balcony. The effect was one of a staggering upwards motion, as if I was about to be launched from a rogue circus canon. It was on this second floor that all the students’ chef d’oeuvres were hung to dry. Mirabelle’s works, however, were constrained to the first floor, and could therefore be observed up close. Whether this was intentional, or the canvases had simply been too large to move upstairs, I didn’t know.

Judgment Day, 1996, graphite

It was in this open, wooden universe that I would undergo The Test. After I had carefully selected my modèle, a macaw on a black background (already in this absence of a surrounding world do I detect the beginnings of Mirabelle’s influence), I was handed an oversized apron and shown to the table with the other kids. Then, nothing. My mentor swept away as fast as she had come, her petite figure disappearing into a mass of students like a small apparition. I was alone with an unprimed canvas.

To an eleven–year–old, this laissez–faire method is nightmarish. In the years to come I would observe the same phenomenon occur with every new student, watching the moment of dreadful realization pierce their expressions, needle–like and deadly. And thus would begin the Darwinian experiment: which of the pink–faced protégés would survive in this world of pungent smells and infinite cabinets? Which would gather the courage to take their first steps?

Sketch 2 of 4, 2052, blue pencil

Every artist must come to accept the fact of their own unoriginality. It is the first, perhaps most essential step of the creative process: to accept the fact that every idea, every thought, every image that passes through their head has most likely gone through someone else’s at a certain place and point in time. Only once this burden of originality has been lifted can the artist begin to find their art. Only then will they create their millionth of treasure, and it will elate them beyond anything else in the world.

Lion Heads, 1996, oil on canvas

It was at break that I bore witness to the most extraordinary ritual. At 6 o’clock sharp, all the students began to drift toward an easel at the back of the studio. On it was a painting of two, enormous, disembodied lion heads. It was one of Mirabelle’s and was regarded, I believe, as something close to holy. Around this time too, shafts of light pulled through the shades and illuminated the portrait in dancing, uneven patches, as if through the stained–glass windows of a church. The whole event ended within minutes, as we then bounced in a similar fashion around the room, gorging ourselves on various displays of technical mastery. By the end of break I was feeling joyfully light and took a few more cookies for the journey back to my seat.

Untitled, 1996–2005, polymer paint on wood

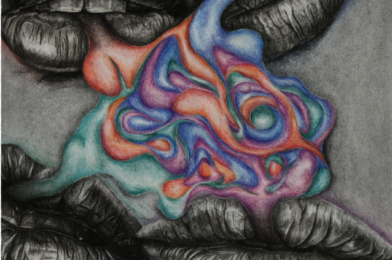

Mirabelle’s work consisted almost entirely of animals. In fact, she specialized in horses. At any one time, dozens of them could be found exhaling their oily smoke into the room. Their sheer realism was astonishing. Yet never would I see her actively work on the beasts. They acquired instead a life of their own, as if mothered by Mirabelle and then left to finish themselves. Quickly my idea of successful art was defined by exactly this: immaculate precision and softness of demeanor. I had yet to realize, of course, that I was being immersed in a uniquely conservative strain of art, a type of art which worked only in an anachronistic fashion, cut–off from modernist influences. Remembering that first day, bent over the box of prints, I had only a landscape or animal to choose from. True, later, the odd modest abstract would appear from time to time, yet it was perhaps in these vaulted flashes that the conservatism revealed itself the most: a flash of light in blazing azure, the swirl of metallic color…

Sketch 3 of 4, 2052, blue pencil

Instead of “art for art’s sake”, I believe the current attitude to be better reflected in the phrase “art for beauty’s sake”. This first struck me while reading the literary magazine of a university in a Jersey town over a summer holiday. The writing was chocked gold, mirroring, it seemed, a garden slathered in sun. It struck me then that plot was a thing of the past. We had returned to the birth of man, a sticky Eden–red creation of God. And to call it realism! But perhaps they were right. Perhaps the world has simply become too ugly to write about faithfully.

A Study of Death, 1996–2005, ink on A4 cream paper

It was the act of painting itself which enveloped me in a state of ecstatic monotony. My mouth slackened; conversation became impossible. I could think of nothing but the canvas in front of me. In fact, all I could do with any kind of success was listen. So, during those long hours of creation, it became common practice for Mirabelle to tell us about her childhood, casting us, it seemed, into a trance of imagist being. The story came in fragments, in a kind of Proustian association that would suddenly come to life and whip us all into the browning living room of a household in 60s Quebec. Her father I imagined as faceless, her brothers fragile. Often the stories were riddled with tragedy, or a violent desire to escape. As the years wore on, I became increasingly intimate with the details of this artist’s troubled past. What struck me most, however, was the incredible disparity between her narrative and her art. Her landscapes were serene, her animals sleek and powerful. Not a storm cloud was to be seen in any of her works. And slowly I understood: it was her way of finding peace.

Sketch 4 of 4, 2052, blue pencil

Years later, I was at an interview when asked about art. The question caught me off–guard, in the way that questions catch you off–guard when you’ve over–prepared something else. I was asked, more specifically, how the written word differed, or not, from a visual medium of expression. Can a three–dimensional, multi–faceted world be expressed in black characters on a page? Can a thought, the pinnacle of an idea be fully formed on a canvas? I still do not know the answer to this question, or whether I will ever be able to answer it. After all, how can one describe art, the most “unsayable” of things?

Sydney Heintz is a senior attending high school in Switzerland and is trilingual with English, French, and German. She is an alumna of the Iowa Young Writers’ Studio and has been published in the Write the World Review. When she is not writing, she can mostly be found learning orchestral parts (too late) and reading her self-curated literary canon, which she hopes she will finish before beginning studies in English Literature at the University of Cambridge next fall.