If a whale shark stops swimming, it dies. Because of their lack of buccal muscles, the creatures rely on obligate ram ventilation, which means that oxygen enters their bodies through their mouths, which then filters to their gills. To get this oxygen in their mouths they have to keep them open, which requires constant movement to keep a consistent supply of new air in their bodies. The more they move, the longer they survive.

I’ve been moving since I can remember. A hurricane baby is what they call kids like me. Instead of being born where I was supposed to, a storm named Katrina came in and pushed me out of what was going to be home. So, while my mother had a C-Section in Yakima, Washington, her heart was left in New Orleans, in a condo under ten feet of hurricane surge. Spray painted X on the door, where no bodies were found and a crib had floated to the den.

In the aftermath of the storm, my family did not move back to New Orleans right away. Instead, my mother and her two-week-old child migrated. Apparently I was silent until we landed, but when we arrived in Oklahoma City I greeted the world with fists raised and screams in my throat. We met up with my father in college housing left for evacuees.

I said my first words in that housing. My first giggle erupted from the back of my throat while sitting courtside at an NBA game. I took my first steps on my first birthday, running toward my Dad in the waddling way all babies first walk. According to my mom, I never crawled. I decided to walk one day, and the new form of movement made itself known from then on.

A year later we moved back home, our real home. New Orleans wasn’t much different. I had been there once before, baptized in a funeral home because it was the only place available, but that was a business trip more than anything else. The same people habited the French Quarter, the same candied pralines and beignets were in supply and the same foul jokes were made. I spent my first Mardi Gras collapsed in a stroller, an empty beer clutched to my chest like a teddy bear. Dog whistle was what they called me later. Mouth always open, always screaming these high pitched warbles that made dogs turn their heads and old women in grocery stores grimace.

The average Whale Shark travels 5,000 miles a year, from Australia to South Africa to the coast of Mexico. They move mainly to replenish their food sources. If they swam around in circles, new food would never have the chance to emerge, so to make up for the 10,000 gallons of water they consume daily, whale sharks make the trek across the shallow end of the Atlantic every year.

I was two when we moved again. Instead of 5,000 miles, I only went 713 to Charlotte, North Carolina. First an apartment, then a condo. I went to preschool and read for the first time.

At three years old we moved into a house. I got kicked out of preschool, learned the tooth fairy wasn’t real and organized a protest against nap time. I bit and kicked and yelled and cried and suddenly dog whistle was not just a funny nickname but a cruel joke. Sound like a dog, act like one, I guess. “Constantly moving” is how a teacher described me. “Too much to handle,” said another.

I stayed in the house and waited for kindergarten to start. When that tried my patience, I went outside and threw some sticks at some trees, but no matter how much I moved I still felt stuck. It was suffocating, and the air leaked from my lungs the longer I was idle. Kindergarten arrived soon enough.

It was the third day of school when I landed in the principal’s office. In an unfortunate miscommunication on game rules, I tried to stab one of my playmates with a stick. He screamed, and I was quickly shoved into the principal’s office to await my punishment. I bounced my leg and bit my fingernails down into tiny stubs of cartilage. When I ended up being brought in and lectured in the principal’s office, my hands tapped on the desk while it was explained to me that I can’t go around hitting other kids when things don’t go my way. Principal Gizzaro’s hands remained still and clasped the whole meeting. I felt bad for her, her stillness. I told her that, but she didn’t understand what I meant. “Just apologize, Madeleine,” she finally said, sighing, which was the biggest expense of energy I’d seen from her yet.

Two weeks later, I made the journey to the principal’s office again, a trans-school hike, spanning from the vibrant yellow of the kindergarten and first grade wing to the dull gray concrete walls of the administration office. This time, my mom sat in the room with me while the principal explained the multitude of ways I never stop moving. I didn’t particularly pay attention to the conversation. I just nodded my head when the adults’ eyes made their way to me, but neither seemed to notice my lack of attention. During the meeting I decided to try and hold my breath for as long as I could, pretending I was swimming underwater, schools of fish trailing beside me. This only stopped when my vision started to spin from lack of oxygen, and for a brief second, it was like I could feel waves crash above me. I took a breath.

In first grade I discovered that when my mouth moves, I feel like my brain moves too. I would yell about the weather and shark facts and Harry Potter and my mom’s cookies. Recess was no longer a physical battlefield to me, but a verbal one, where I was armed with a barrage of fun facts and stories to use. This development eventually proved to be a problem when my teacher had to continually tell me to stop talking. When I finally got the message, I began to hum instead. When she said to stop that, I tapped my fingers on the desk until I was sent into the hallway. I wanted to tell her that I couldn’t help it. Without movement, I suffocate on my own air, feel waves crash above my head.

Whale sharks are slow creatures. Despite their great travels, they only move up to 3 miles per hour. If you were to put the average speed of a great white shark (5 mph) up against the whale shark, the great white would have more than doubled the distance of the whale shark in an hour. Because they’re slow, whale sharks, when maturing, fall victim to other, faster fish, like the blue shark, known for its haste and ability to stay still and camouflaged for long periods of time. They prove to be some of the greatest dangers young whale sharks face in their life.

I’m told from second andto third grade were quiet years. The phrases “aA pleasure to have in class” and “kKeeps to herself” made frequent appearances on my report cards. My teachers were happier with this development, as were my parents, so instead of my tapping and humming and talking like before, I quietly bounced my leg up and down, not drawing attention, just attempting to float through the rest of my schooling. I discovered that the sound of a pen against paper was similar to the click of a keyboard, and when my hand moved, writing out stories in sprawling handwriting, air came a bit easier to my lungs. With this, my camoflauge seceded and my movement resumed.

Writing happened to be the only thing that kept me moving, and that came to a skidding halt the first day of fourth grade when my teacher did not find my constant scrawling to be productive. She decided that my stories were deterring me from my schoolwork and confiscated pencils until I needed them for math homework. Stripped from my newest resource and desperate to be moving once again, I began tapping my piano homework onto the glue-stained desk in front of me. Melodies of Mozart and Beethoven playing across social studies classes and quiet time. My teacher, once again, did not find this as amusing as I did, and would glare at me from across the room or yell my name at me until I stopped. For the first time, my grades were not just a row of A’s and 100’s, and there was no clap on the back for the extra effort put in to fix it. There was no movement. I was suffocating once again, sitting like prey to be taken advantage of. Weak and defenseless to the other fast moving animals in my environment as waves crested above.

When threatened, whale sharks have one defense to fall back on, their three thousand one-inch teeth. Typically reserved for eating small shrimp and plankton, the teeth are not useful in violent situations, but there has been evidence of whale sharks attempting to use their teeth when threatened.

In the fourth grade I bit a girl named Sophie. She was tall and scary and loomed over me. She had nails sharpened like claws and always managed to escape the eyes of teachers when she used them. A master of camouflage. It was on the playground where I attacked her. She pushed me off the swings and, cornered by her against the black iron fence. I couldn’t breathe. Sobbing and shaking, every bit of oxygen seemed to escape the air around me before I could take any of it in. I desperately gasped for breath as she laughed at me, my back stuck against the fence and feet firmly planted on the ground. She reached out her hand toward me. I bit her.

Whale sharks are remarkably peaceful creatures. They travel in diverse groups of fish, develop relationships and only eat what wanders into their mouths. Despite not traveling in groups with each other, they find community within other species and benefit from one another. It takes a very specific creature to travel with whale sharks though. They have to be willing to put up with traveling five thousand miles in three years, dealing with the whale sharks size and power as it maneuvers through the sea, but most of all, they have to be able to move alongside the gentle giant.

I still have trouble breathing sometimes. My chest gets tight and my head begins to float as I feel stuck underneath the break of a wave, trapped between thick white bubbles fuzzing up the water. I tap imaginary piano notes onto my thigh when nervous, bounce my leg and run my hands through my hair. When I’m not doing that, I’m talking. To myself, to my friends, to the air, whoever will listen. And when I can’t do either, I begin to asphyxiate. As long as my heart is beating and my brain is running, you can count on me to be in motion. That motion is not always consistent. Some days I move like an Olympic athlete, on others I keep a nice slow pace. The difference in speed depends on my company. In a room full of unfamiliar faces, I ricochet off the walls, hands tapping endlessly as I look to find something to replenish my air. But when my mom holds me as we watch TV, or I go on a walk with some friends, taking in the crisp autumn breeze, I move slower than ever.

Whale sharks can slow themselves down to half a mile an hour and still survive just fine. Oxygen flows into their gills and filters itself at a healthy rate, and they are well. The main occasion they do this however, is around their community. When their companions are with them, swimming right alongside, they slow down, moving at a comfortable pace for everyone. Marine biologists have reported this as a sign of love in whale sharks, moving at a speed which best suits the ones around them, a compromise. The company could move on and survive without the whale shark, and the whale shark can do well without them, but they make the choice to stay together, working at the same speed.

I know I’m in love with someone when I slow down around them, and they slow down for me. I know I love someone when my hands shake and they understand and hold them anyway, and when my brain moves quicker than a bullet, they try to follow it. My love is a live, breathing thing. Composed of the constant ups and downs of a chest, containing the lungs, the heart, ever moving. Love for me is not absence of motion, it’s who I am.

Maddie Thompson is a 17 year old writer currently attending the South Carolina Governor’s School for the Arts and Humanities for creative writing. She enjoys writing comedy pieces, poetry, and personal essays, many of which are about media she enjoys like comic books and rock music. Her favorite things to do are play guitar and watch movies, specifically heist movies.

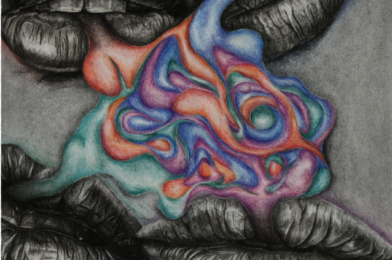

Visual Art by Carina Wang

Tagged : creative non fiction / experience / growing up / Maddie Thompson / memoir / whales