I was eleven years old on my first ballet lesson. I can still remember pressing my nose to the cool glass of the car window, waiting for the imposing white structure of the academy to glide into view. My mother was prattling on at the wheel, telling me about how she used to just love ballet, how it would make me graceful, how someday I’d become a celebrated dancer and perform on majestic stages in glamourous cities before spellbound crowds. I’d stopped listening for a long time, but she didn’t seem to mind. I just leaned my head against the window and let her lilting, fervent tones carry me away. At my young age, I couldn’t put my finger on what it was that rankled me about my mother’s chatter. It wasn’t that I was nervous, really, or reluctant to go. It was only until many years passed that I realised. It was that everything my mother had said, the way she’d said it, reeked of self-regard. Selfishness. She didn’t want me to go to ballet because it would be a fun extracurricular, or because she wanted me to learn a skill. She wanted to vicariously experience it all for herself.

The thing was, I’d never been a child who did or was anything. While other children screeched and tore around the house, I pottered about alone in the garden, seemingly at one with the silence, apparently completely content. While the girls in my class joined ice-skating or gymnastics teams, or learnt to sew from their grandmother, or played wild games of Tag in the playground, I stayed as silent and meek as ever. The only times I opened my mouth was if I ever needed anything, and I rarely ever did.

It unnerved my mother. She had grown up sprightly and healthy and completely happy, and it worried her to see the seeming lack of spirit in me. The lack of anything in me. I was an average student at best, prone to fits of daydreams. I had friends at school (who were really only loose acquaintances) but only because I was content to do anything they asked of me. Worst of all, I was terrible at every single hobby she tried to push me into- first it was the piano, then horse-riding, piano again, then acting, of all things, (that was an indubitable fiasco). After each attempt failed, after hundreds of pounds spent for months on another activity I showed no signs of interest or improvement in, my mother’s face would pinch like a clenched fist whenever she looked at me. She would almost snap on the rare occasions I asked her anything. Sensing danger, I would withdraw even further into my little world.

Now, sometimes I find it hard to fault my mother. She expected mothering a daughter to be tying ponytails, and trying dresses, the euphoria of childish hugs, and the responsibility of wiping away precocious tears. What she got shocked her, I think. It certainly removed the rose-coloured glasses from her eyes. She wanted to look at my youthful face, and see a promising child, a child who’d go on to make her proud. A future architect, teacher, leader, lawyer, mother. Instead, what she got was a child she could understand no more than if I’d been on the moon. And when you feel such a deep, all- consuming dissatisfaction with your child, they will know, inevitably. Subconsciously, I think I always feared my mother’s disapproval. And so I withdrew.

I understand that she felt that I was inadequate, mediocre, and my mediocrity made her inadequate. As a mother, as a thirty-seven-year-old whose achievements were now over and irrelevant. In fact, I sometimes think that she’d rather I were stupid, or arrogant, or a plainly unpleasant spoiled brat. Anything other than the way I just existed. At least she’d have something to show. Now her child was who people saw when they saw her. I was a representative of her, an ambassador, without even realising it. And I clearly wasn’t meeting the mark. That was what led to the ballet. My mother still had some lingering hope left for me, and so she rambled on at the wheel.

Although I was vaguely aware of my mother’s frustrations, the full situation was far too nuanced for my mind to grasp until years later. My annoyance didn’t last long, and there was no resentment in my heart as we walked to the academy after parking the car. And my memories of that first ballet lesson are certainly not unpleasant. I remember a tall, angular woman with impeccably smooth skin and a very pink, lipsticked mouth meeting us at the door. She wore a black leotard with dance tights and greeted my mother with a bony hand and me with a cool smile. I felt very small under her gaze, unconsciously straightening my posture. Her eyes pierced like needles as she looked at me from that great height, as though she was sizing me up, assessing my value. She introduced herself as Madame Martin, leading dance instructor at the academy. With the natural instinct of a child, I knew from a glance that this wasn’t a woman to be messed with.

Madame Martin led me through a narrow corridor, and then opened a door and prodded me to enter. The intense white light dazzled my eyes as I stepped in. Blinking rapidly, the room swam into my vision, and I was stunned by the display that I saw.

Tall, willowy, swans of girls in fluffy tutus were swooping across the wide practice floor, pirouetting, spinning, leaping. It made me dizzy to watch. Their feet flew with easy elegance, their hands floated with a gentle grace, all in perfect harmony with each other. If they were tiring, you would never have been able to guess it by their radiant smiles and starry eyes. With each step, their tightly laced ballet shoes pounded the floor in perfect unison, creating a perfect beat of their own over the fluting violin piece. Those that were not dancing were stretching their slender legs over their heads in front of the long mirror. I could see the supple muscle rippling like water under the skin. The whole room was a lively flutter of femininity, all soft skin and sweet smells and hairspray. Through my transfixed eyes, everything shone with a pure glow that seemed natural and right. Like dewdrops shining in morning sunlight.

Looking back on this memory, preserved perfectly and dreamily in the front of my mind, I think I had had an epiphany of some sort. For the first time in my eleven years of life, I wanted to be someone. With all the strength in my little heart and from the marrow of my bones. And for the first time, at eleven years old, I realised just how small, how insignificant, how utterly unsatisfactory I was.

I felt like my heart would stop beating when I thought about learning in front of them. I’d stumble about like a fool. Would they all glare at me, at this odd, small child who dared join their ranks? Would they laugh, looking down from the lofty heights of superiority?

The feeling didn’t last long. After letting me watch for a minute or so, Madame Martin pulled me out of the room. She must have read the expression on my face and guessed at my thoughts. In a surprisingly gentle tone, she explained that I would be in the beginner’s class, that those girls were training to be professionals. “If you work hard and practise,” she told me gravely, “you might make it too.”

And I did. My whole life now revolved around the dance. Even throughout the week, ballet was constantly at the back of my mind- at school, I would absently dance the steps in my head, try to recall the technique. Madame Martin’s words echoed in my mind. “If I work hard…”

Every morning and every night, I would do my stretches in my room, feeling fierce satisfaction as I steadily got more flexible. Whenever Monday drew nearer, it would become almost obsessive. I threw myself into all the classes with a passion. With every mistake, every slip-up, my legs would turn to water, my throat constricting. I’d flash a guilty look at Madame Martin, searching her eyes for disappointment. But all the errors did was make me more determined. I shone amidst the other girls- and I knew it. Before long, I could dance any piece flawlessly without any hesitation. I moved up two grades in what seemed like no time at all. Sometimes, I’d look up and see a fleeting glimmer of pride in Madame Martin’s usually cold eyes. Inwardly, a shiver of glee would run up my spine.

My zeal was not for the girls at school, or Madame Martin, or even my mother (who was, of course, delighted beyond words). It was for me. I could never go back to being who I was. I was on a journey now, a journey that I was determined would end in the room with those beautiful dancing girls I’d seen my very first lesson. A journey from Nobody to Somebody. I was certain of one thing- I would never let myself be Nobody again.

Gia George is a 14 year old writer from Chelmsford, England. She’s been writing ever since she can remember. If you’re reading this, she’s probably at school, doing homework, writing, or reading.

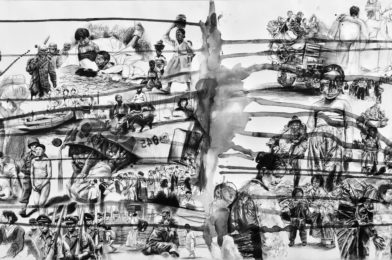

Artwork by Anastasia James