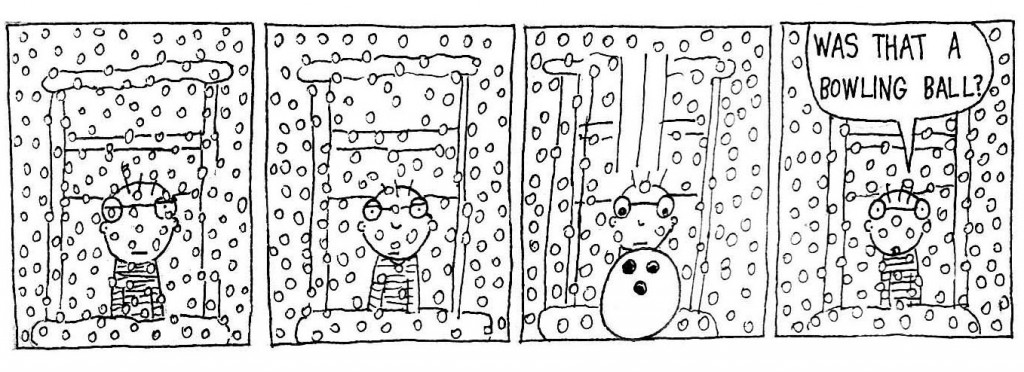

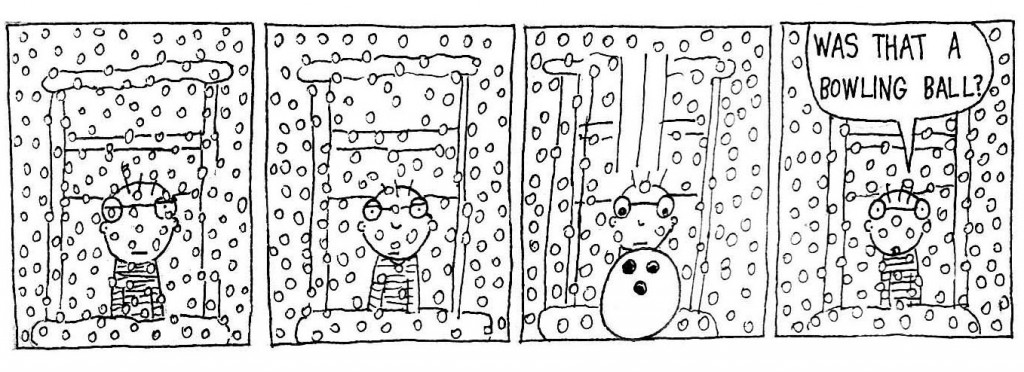

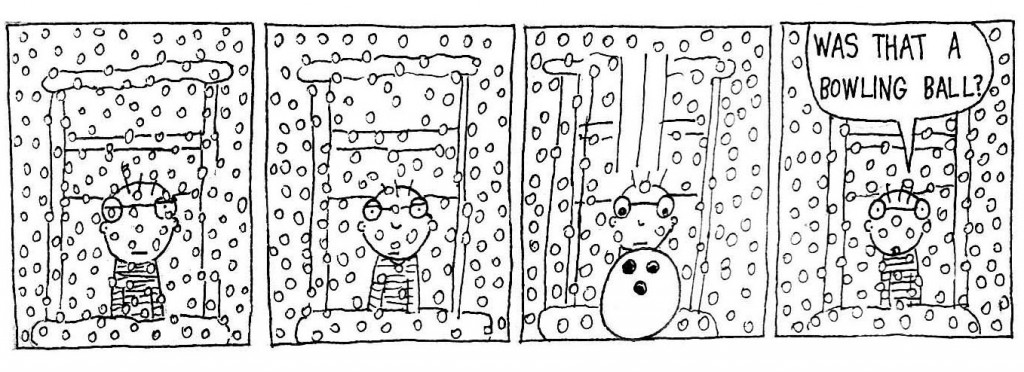

Heavy Snow

Visual art by Ben Mcnutt.

Ms. Lucy Hatchett had always wanted a dog, and throughout the years living with her father, he had always told her that if she got one

“I sure as hell am not going to pay for it. They’re too much money, they make you waste away your life at the god-forbidden vet’s office, and they take too much time to keep in shape. That’s not to mention that if any goddamn kid walks by and has a disagreement with the bitch, and he gets bit, then you’ll have to deal with some bullshit government lawsuit. Those pansy government lawyers always have their hands in my pockets.”

The old Mr. Hatchett had long been a radical conservative, with a history of tax-evasion and numerous DUI’s. The federal court filed numerous cases against him around the time that he died, and once they were settled, the fees were large enough to take away any inheritance that Lucy and her brother would have received had they had not been incurred.

So, because of her Father’s enjoining, Lucy denied herself one of the biggest wants of her life. That is, until she realized that she didn’t have to anymore, on her sixty-second birthday, on October 10th, 1982.

It was an absolutely dreadful afternoon. The streets were swallowed by a blustering wind, and having recently broken her cane, Lucy found it near impossible to traverse the city without clinging to the buildings. Her pension check for the month had just arrived in the post, and along with it the bill for her brother’s cremation, who before his death had been her last remaining relative. Her brother had really been the only person in her entire life who she could honestly call a friend. They had been through their entire life together, right up until Charles joined the army. Because of his extraordinary military talent, the service had promised his sister and him a completely paid for college education. He was happy about this, as it meant they could both rise from the depressed economic status they had so long inhabited.

After the war, however, Charles had proceeded to get extraordinarily rich through the entertainment industry, as he became a show runner of a highly successful television show. He had managed this after saving the life of one of the Privates under his command by performing an in-battle emergency surgery, entailing the incredibly gory removal of a fifty caliber bullet from his buttocks. The Private, left eternally grateful, had then asked what could be done to repay Charles, and said that his father was a television network executive and he could get him an interview. The interview went spectacularly, certainly the circumstances helping, so Charles was assigned to a new, sure-to-be-hit show. He then married and had children with a French woman named Élise, who happened to be playing the title role on Charles’s show, and she absolutely despised Lucy. Maybe it was Lucy’s awkwardly positioned nose, her fascination with kitsch and deco art, her habit of forgetting everything, which she had developed even before she suffered from dementia – but whatever the reason, Élise mandated that as long as she was married to Charles, she would not take the aesthetic insult of having to lay eyes on her. They didn’t, and immediately after Charles’s fatal episode of pulmonary edema, Élise found it classy enough to simply forward the hospital and cremation bills to Lucy, while she enjoyed the life insurance.

Lucy had just finished paying off the bill for the emergency room, and you can imagine how thrilled she was once she discovered that she had been sent the one for the cremation as well from her darling and most esteemed sister in law, Élise Beaulieu. Lucy was feeling lonely, desperate, and distraught over this chain of events, but as soon as she walked around a corner coming home from the post office and saw the Good Times Pet Rescue Center, a light went up on her face.

Inside the Center was a cage of howling, yapping, pit bulls. They rustled around in juvenile tomfoolery, and one particularly rowdy pup found it amusing to pounce on the smaller ones and harass them with youthful skullduggery. Ms. Lucy Hatchett was absolutely enthralled by them, and spent a solid minute observing the nuances of their coats – one was shockingly white, another night black with a white eye spot, and yet another was completely chocolate brown. She noticed some foamy spittle emerging from his mouth, but figured it must be merely drool, and not anything contagious. She entered the center and immediately approached the adoption counter, leaned over and said to the clerk,

“How much for the puppies?”

“How many do you want?” He replied.

“All of them.”

“Well…sixty dollars each.”

“Still, all of them.”

The clerk, obviously of significantly inferior intelligence to the average person, gave Lucy an expression of complete and utter disbelief. He managed by shifting his face in such a lucid way it was almost as if you could see the gears clicking together, to issue a quieted and slurred:

“Wow, Lady.”

Lucy had no patience for the clerks mundane babbling, she was buying dogs, for Christ’s sake; so, making the calculation of six-hundred-and-sixty dollars herself, judging it too intricate a task for the clerk, she wrote a check and pushed it across the counter. She knew at this point that the only way she could afford this as well as all of the other expenses that would occur upon her in the next month, along with the cremation bill, would be to get a Pay-day loan – one that would charge her exorbitant interests so that she would probably never be able to pay off, except perhaps, post-mortem. But, of this she was nescient, and so she didn’t care – she figured that she could just pay it off next month, not realizing that when next month came around she’d have to be paying off an entire new set of expenses. Pushing the simpleton to carry on again, she said calmly,

“Here, now just give me all the paperwork to sign so I can get back to my flat as soon as possible.”

After many minutes of fluttering signatures and glancing over legal papers and the clerk mindlessly shuffling around and continuously handing Lucy the wrong documents for signage, she eventually made it out of Good Times. Lucy, and the crate of all of her newly purchased dogs, were going to be driven back to her address at 561 C, Grange street, by the shelter shuttle, but as complications arose involving the driver, that was no longer an option. The complications being that the driver had pretended that he had chronic bronchitis as an excuse to explain why he was “unable” to transport Lucy, while in reality, he had just taken a lovely F.O.B. Italian woman back to her hotel with her new poodle (Good Times Good!), and had then arranged a date at the local Thai restaurant for Saturday night – he figured that there’s a minimal amount of garlic in Thai. The reason he had claimed illness to avoid transporting Lucy was that for him, a hip and groovy young man, to be transporting some nasty crone was on-the-job social suicide. So, he left her to her own devices as to transportation to her residence.

In a slight flummox, Lucy sucked up her frustration with the young buffoon, and trotted out of the door with her dogs. As she exited the premises, a rank odor began to emanate from the crate. She had not noticed it before, but the inside of the crate that she held the puppies in was covered in their excrement and other sorts of bodily fluids. It had obviously never had been washed once, and so not only was it covered with the newly produced soil of her dogs, but also the excreta of all the dogs before them. Lucy wondered if the people at Good Times had done anything correctly anywise – whether they’d given the dogs their shots, had them fixed, etcetera – and came to the conclusion that they probably had not, given the presented intelligence of storefront employee.

While on her way back to her apartment, traveling down the streets of her city, Lucy, with the box of yipping puppies, came across a large patch of black ice on the sidewalk. Her visibility was impaired by the size of the crate, not to mention the already-acquired hindrance of the blustery wind. As she came across this patch of black ice, she had absolutely no idea that it was there, instead, it merely happened upon her; so down she went, landing on her already sore back and her rump, letting loose of the crate and having it slide down the sidewalk a few feet. All of the people that walked by her merely stepped around her and her dogs, ignoring the dilemma that they faced. One of the pedestrians actually kicked the crate into the building Lucy had fallen next to to remove it farther from their beeline. Lucy did manage to get back on her feet, but needed to spend the rest of the journey back carefully traversing the various sections of imminent and immediate danger that plagued the path. Once she did, after much arduous questing, arrive home, she set the dogs loose in the house, allowing them to fulfill their every will to roughhouse. After doing so, she collapsed with exhaustion onto her couch, as she had not eaten all day.

So, to solve this problem, Lucy then went out for a quick trip to the Pay-day loan center to get an advance for next month, then the bank to deposit her pension check and the Pay-day check, and then to the corner store to get some food for her and the dogs. She had absolutely no idea of the quantity of food that was necessary for eleven dogs, so she simply purchased an entire case, and while in the process of buying the dog food, forgetting to buy food for herself and even the fact that she was hungry. The cashier asked Lucy if she would like a ticket for the next national lottery, and Lucy did. She then bought one with the same numbers she’d been using as long as she could remember, 101082, and then left the store to go home. After returning to her apartment, carefully placing the case of dog food by the door and the ticket inside a drawer of a nearby dresser, she found that every single chair in the apartment had been knocked over, that all the kitsch on her coffee table had been smashed to bits, and that dog hair now inhabited every surface of her house, and let out a blood curdling scream that could’ve given any person an aneurism. However, she quickly recovered from her initial shock, and resolved that she would speak to her newly acquired pets, in a simple, parental manner.

“Come here, puppies!” she called, in a faux-gleeful manner, to which, surprisingly, all eleven of the mid-size pups came barreling into the room.

“Now look here,” she said in the relative tone of a pretentious vice-principal, “I know that none of you have probably had a parent before, so you’re unaware how this is supposed to work. You should know that I’ve also never been a parent myself before this, so you might need to cut me a break, now and then. So, here are the rules of the house:” (She now began a series of confused facial maneuvers, perfectly fitting to her following impromptu postulations. Absent minded cheek biting, lip curling, single brow wrinkling and so on, with vocal inflection to match the movements.) “No sitting on my chair. The red leather one. It was a gift from my brother, and your hairs, I’d imagine, are dreadful to clean. Also, no TV after seven. I’ve got to take my Lisinopril at night, and it makes me very sleepy, so the noise from the TV just gives me a headache. I’ve got a bad heart, you see. That’s why I take my Lisinopril.”

The dogs, at this point, were observing her intently, watching her soliloquize as if they held what she said as a matter of the utmost importance.

“Third,” she continued, “Is that you may not go out at night. Also, no sleepovers, is that clear with all of you? I expect a nod from everyone.” The dogs moaned.

“Good enough. Alright then, off to bed. It’s late.”

It was, in fact, only seven, but, as the day of rushing about the city and picking up the dogs from the shelter had worn her out, she went to bed, forgetting to feed both the dogs and herself. She, aside from the little disaster in the setting room, was rather satisfied with today’s events – maybe these delightful little dogs would help her make it through the rest of life, week by week. At least, she hoped so. They nipped at her heels as she walked into her bedroom, but as soon as she took out her hearing aid, the building seemed, to her, as calm and tranquil as a pastoral lake.

* * *

The following morning, Ms. Lucy Hatchett awoke not to a blood curdling noise, but to an earth shaking rumble, startling her to consciousness. She quickly donned her hearing aid, rocketed out the bedroom door, and found that two of the dogs had been fighting, the chocolate brown one and a white one. The brown one had prevailed, broken its opponents neck, and had proceeded to eviscerate it. The remnants of the cadaver were being ravenously swallowed by the rest of them Lucy panicked, and for a moment was stunned, trying to figure out what way was best to navigate between the dog kidneys and intestines, lifting her bare foot up, almost putting it down but just in time realizing that what she thought was linoleum was actually stomach lining. The pups, in particular the brown one, mistook her surprise for anger and shriveled into the corners, leaving the mess of organs alone as she stood there – almost as if they expected her to beat them.

Eventually, Lucy sucked it up and ran through a patch of floor, still soaked with blood, but had just had the piece it had been covered by stomached by a dog, and booked out her front door in her pajamas. She went to her corner grocery store to buy another case of dog food, forgetting about the case that remained untouched in her apartment. She was also convinced by the cashier to buy another national lottery ticket, number 101082. And again, she went off to her home.

Upon arrival to her apartment, she set the case down next to the door next to the other case, crammed the ticket inside the drawer, and yelled for the dogs to come. She then began her second monologue as a pet owner:

“Now listen. This. Is. Unacceptable! I know that you were hungry, but family is family! I never really had a good one either…my father always would tell me that I was useless, and that his want for me was about as equal as that of his want of a dog…but he was a terrible man. I’ve always wanted dogs, you know, my entire life, I figured they’d be such good companions. I hope I was right…but, I guess, dogs are like people. People are never very kind to each other either, you know. Most of the time. Especially the ones I’ve known. I’ve always read about the greats of our world, the Nelson Mandela’s and Dr. King’s, but I’ve never met any. Anyways, you should learn to get along with each other. Just remember to eat, so that you won’t get grumpy!”

By this time, poor old Ms. Lucy Hatchett had again forgotten that she had purchased food, and again forgot that she needed to feed her beloved dogs, and carried out the rest of the day on her usual routine. A quick stop down to the Congregationalist church to do some volunteer work involving organizing old sermon papers, which she had absolutely no clue as to why she was doing, then, a trip to the grocery store to pick up the night’s dinner (chicken, rice, and green beans), and then went back to her house, already completely exhausted, to curl up in her red leather chair to read Brontë’s Agnes Gray, for the umpteenth time.

Recently, Lucy had been becoming more and more upset. The dogs, although she still loved them, had not successfully filled the hole in her life that she had hoped they would. She had always lacked a family, since the departure of her brother – never having gotten along well with her parents and having been single her entire life. Except for the dogs, she’d never truly loved anything or anyone – and even them, she had still yet to name, as she continually forgot that she was “supposed” to.

She didn’t really have many friends, either – there were the old crones at the church worthy only for gossip-mongering, their husbands alive and well, and making sure that Lucy knew it. There was the young postman who always gave her a smile, while stealing her Netflix deliveries, the sweet young lady cashier down at the grocery store who sold her 101082 multiple times a week for the same lottery. There was also a pharmacist who had taken her out to coffee once, fifteen years ago, the month after her father died. He’d wanted to ask her out ever since they’d gone to middle school together, and simply had never bothered before because of the frightening nature of Lucy’s father; but even he was shrouded in bad intentions, as recently, he’d been trying to figure out a way to sneak Rohypnol, or another genus of date-rape drug, into Lucy’s monthly batch of Lisinopril. All of the people who claimed to be her “friends” really just wanted to exploit her, in one way or another – although, Lucy remained painfully unaware of all of it.

There was no one in the entire city who gave a single damn whether or not Lucy was alive. This was because no one ever paid attention – she was allowed by the community to rot, to become a living shell of a person, someone only worth extorting, to the point that no matter how hard she tried, she could never become healthy again on her own. And there she was, with her dogs, signed over to her without them being tested for or given shots for any standard diseases. They might as well have had rabies, they had been so mistreated by their previous owners and the employees at Good Times.

It was because of this, paired with her impending age that Lucy had been sleeping longer than was healthy – upwards of thirteen hours, on some days. So, by the time seven o’clock rolled around, she was 150 pages into Agnes Gray and already half asleep. Then, again forgetting to feed both the dogs and herself, she wished them a good night, sweet dreams, swallowed the gaping hole in her soul, and went to bed.

* * *

The next morning, yet another dog had been killed and eaten by the Chocolate brown pitbull. And the next day. And the next. And the next. Ms. Lucy Hatchett resolved to buy a new crate of dog food so that they wouldn’t attack each other, again, and again, and again; Lucy also forgot to feed herself and the dogs, again, and again, and again. A permanent blood stain resided around the kill spot, which Lucy dutifully cleaned. That is, until ten days after her birthday, ten days of not eating, and ten days of finding dog carcasses in her hallway every morning.

On October 20th, 1982, Lucy awoke at ten a.m. She entered the living room to make herself her pot of morning tea, and began to read Agnes Gray, yet again. While she did so, the Chocolate-brown pitbull came out of the living room and into the kitchen, quietly and with guile, to watch his Mother. Her pot of tea was done now, and she dutifully fixed it up with a cube of sugar and a splash of milk. Then, she went over to her cabinet to grab a cup of water and her heart medication from her shoulder bag on the counter. At the counter, when she pulled out the bottle of Lisinopril and tried to open it, she found that she was too weak. She tried and tried again, with all the strength that she had left, and with her last ounce of energy, made the bottle relinquish its cap. The strength it took to do so, however, was the last bit in her body – she collapsed to the floor in exhaustion, letting loose of the bottle as she fell. The bottle of Lisinopril, now open, had scattered its contents all around the kitchen floor.

The last remaining dog of the eleven that Ms. Lucy Hatchett had adopted, the chocolate brown , now made its way into the kitchen. It then, slowly and without any tarrying, continued into the kitchen, foaming at the mouth. Seeing the dog in its condition scared her to bits and pieces – that combined with her ultimate exhaustion is what led to her simply passing out. The dog proceeded to raze Lucy’s half-corpse in a frenzy worthy of a Norse Berserker, annihilating every single shred of her, leaving behind nothing but gnawed on bones. He then spied the small, pinkish pills spread around the floor, and gulped up every last one of them. But a half hour later, he began to stumble around sleepily, leaving behind him a trail of diarrhea and expectorant. He wandered around crashing into furniture, and eventually, out of exhaustion, also became inert at his mother’s side. They, Lucy and her beloved dog, were not found until a week after their deaths. By then, a pestilent smell had taken over the entire neighborhood, and left an imprint as to where the world had failed them both.

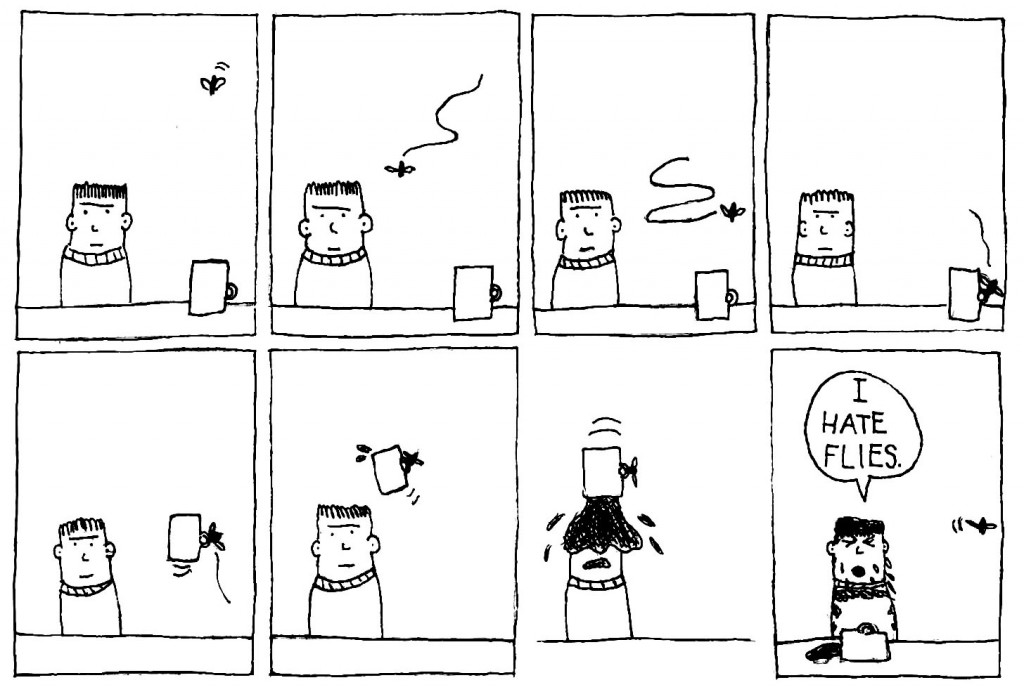

Visual art by Sarah Abrams.

Inspired by Lorrie Moore’s “How”

Begin by answering the phone, reaching into the mailbox, visiting your mother. Maybe you hear it over the radio. Watch a late-night special. Read the back of the non-fat milk carton. Outside your building, your mother will apologize repeatedly. She will cry. She will have had her long grey hair cut short. A gesture.

Four years, one month and three weeks. You left your daughter, husband, and high school sweatshirt in a dusty village – village, really – in east Missouri. Your mother tells you that you will have to go back. She’s full of bright ideas these days. Feel abandoned, frozen, terrified, frantic, and the hottest little brushes of rage. When desperate or alone, walk to the grocery store. Stare at the backs of milk cartons. Blink at her name, age, height and wide eyes or, alternatively, hurl the stupid Missing Person ad to the ground. The night manager drops your arm when he figures out you’re the kidnapped girl’s mother, or he fizzles out of the room when the police officer fills him in. Either way, they tell you that you get to go free and you spit on the parking lot floor. Four years, one month, and three goddamn weeks, but you’ll never be free.

Make attempts at finding your ex-husband. Remember: you left him not the other way around. The operator will ask you for the city and state, please. Tell him bitingly, bitterly. Add: it’s a hellhole, a fucking waste, I mean home and all, but a pit. Devotion, deep-rooted and hot, laps at your insides. Explain the lack of options, lack of exhilaration. Plan not to hang up until the call goes through, but have a text message of the number sent to your phone just in case.

And yet from time to time you will stare into the bathtub or a random tube of lipstick and bask in the life you have cultivated. You will feel nips of contentment, exultation, joy. Four years, one month, three weeks, and this is your family now. Let’s say your father is a troll. Your ex-husband is a magical turnip. Your high school classmates are spirits of the netherworld. They all still live in that primordial tar pit together.

Her name means rival. Once she leaned over you while you were flat on the floor between sit ups and kissed your forehead like she understood the gesture. She is velvet Teddy bear bow ties and creamed corn and knit hats and fly-away balloons. Once upon a time a tiny fist pounds into the carpet and you dance over to her spot on the floor, into her bright little soap bubble, “Up Mama I wan go up.”

Lie. Tell your ex-husband you work in a museum, one filled with taxidermy animals. He wants to know about health risks. He wants to be sure that you’re, you know, all right. He breathes heavily into the receiver. Lie, repeatedly. Say you never have to work night shifts, that your darling grandmamma of a boss never makes you. Darkness. Glass cases. Chrome door panels. They all still scare you. He wants to see you. He wants you, ravenously. Do you still only fly United?

Don’t put on music. Don’t wear lingerie. Take off your clothes, shyly. It’s a craft. You will lie on the bathroom floor naked, watching, your fingers beseeching bare skin of his insecurity. Hair: fool away from his face. Buttons: charm out of their hidey-holes. Chuck his shirt in the corner behind the toilet. Roll him over on your old bathroom floor barely three hours after your night flight lands, just past dawn in Hell.

Go to the front porch. His neighbors. Everyone will look at you and then go back to what they were doing. His best friend’s wife will be jostling a toddler over her shoulder as she walks past. She will introduce herself as Tammy. Try not to laugh. She will want to know if Harold is home. She will ask you, “Are you house-sitting for him?” Faintly, distantly, she’ll remember the junior prom when you stuck celery sticks and Ranch dip down her dress, and look quickly away. You’ll smile. The toddler will spittle over the back of her pink and yellow blouse: gurgly, gaping mouth and hazy eyes push up into her neck. Feel sated, to the point of excess. “Is Harry home?” she’ll ask you again. Smile. Shrug. Swat the door shut behind you.

It intoxicates you. Self-satisfaction. A slurp of tequila. When you pass women your age on the street, giggle and stare them straight in the belly button, straight in their bulbous, lactating breasts.

One day – in a movie theater or a hardware store – see your father. He is either balding or sun burnt. He still has his special belt buckle from the car show at the fair and this will seem almost spiritual . Have sex with him once and lay spread thin on the floor of your childhood bedroom, since converted into his trophy room. Or: don’t have sex with him. Hide behind the shelves of all the different sized hammers and then run for your life.

In the kitchen that weekend feel loud and relentless. Sit on the counter and tell him he’s ugly. That you bet he doesn’t know shit about cars. That you’ve come back to find him freckled and spineless. He will give you a momentary view of his hunched back, vertebrae poking through his shirt almost like fingers stretching through a balloon. He will start to shake. Rub your hand up and down his arm. Run your fingers through his hair.

When you get out of the shower, damp and smooth-skinned, conquer his chest with hard, heaping bites. Trace your big toe against his ankle. His inner-knee. His uniform is slopped over the bedpost. He will push you so hard you stumble and smack onto the floor. Say something like: What the fuck is wrong with you? Or maybe that’ll be his line. Go back into the bathroom. Tighten every cap.

This will be the tough part: her name repeats on the radio, at least on the station your ex-husband always plays; her name, age, height. On restaurant windows you see the posters. In line at the pharmacy you get furtive looks. They form a support group for you. They touch their own children’s heads. Bang the toe of your boot on the corner of the pew on accident. A cuss shoots through your lips like a little fish. He ducks his head and rubs the back of his neck, standing in front of the pastor sputtering search plans and statistics. Stare him down the next Sunday. Dare him to invite you to church.

Your ex-husband will have a sister named Susan. Or maybe an ex-girlfriend who wears socks with white lace around the rims, even though she’s like thirty or something. At visits she will touch her ponytail and repeat herself. She will tell anecdotes about your daughter’s childhood when he goes to get you two girls something to drink. And she’ll call him honey pie. He will agree with her: yes, the police should be much more involved; yes, there should be television advertisements too; no, no, they should never give up hope. She will take out her hair tie and shake a hand through her thick strands, glancing at you. He will invite her to stay for dinner and walk her to her car when she declines. He is the best honey pie in town.

Think about leaving. About standing in a damp-smelling elevator and being all drippy. Think about them: the endlessly illuminated street signs.

But it’s cold, New York, and it’s wet. And he tells you his mother cooks this unbelievable roast turkey, somehow you never got the chance, back before you left, to try it.

No, you wouldn’t leave before Christmas.

Escape into movies. When he calls and asks you what you’re doing, say “Keeping busy.” Let your eyes roll back to the screen. At around 6:40 start listening for his car and when he pulls up, switch off the TV. Head back into the bedroom. Leave the DVD in, though. If he checks, he’ll catch you doing nothing wrong at all.

He will seem to be drinking Vodka, tentatively, glancing quickly at you for approval.

At work he will spend company time in the exercise room.

He will ask you if you want to go to the fair.

He will ask you what the symbolism means.

Well?

Four years, one month, three weeks – more now. Tell him it’s complicated, what with your daughter and your job and your forwarded mail. You no longer know what you want from your life. When he brings his arms to you, open, tell him you don’t even know what you want. Don’t fucking cry. Get a little carried away. Plan to regret this moment, someday. Pace around the kitchen and tell him you are anxious, all the time afraid.

But this is your home, he will say, in a voice that rights wrongs and slays dragons, that dies off after the Middle Ages or maybe exists eternally in the bottom drawer of the pantry where you keep plastic bags for unforeseen situations that might require plastic bags, a voice that shoves the door open with its head, knocks back its visor and wails, knocks you out of mental tangent, wailing: How long has it not been enough, why didn’t you tell me it wasn’t enough?

You will forget the last time you went barhopping in Hell, but pretend you do. Reminisce until your pupils shrivel up. Choke up. Say: I’m going out. And when your ex-husband catches you at the front door, add: Just out. His limp smile will palpitate like an upset stomach and you will hate him. Don’t bother to shut the door. It’s the Pig’s Squeal and it’s just how you pretend you remembered: smoky and wooden and dim like a copper penny. A bulky jukebox and a half-empty jar of straws. A man in a red tie will catch your attention and then drop it. Someone on your right will start mewling the lyrics. Swivel on your barstool until she’s finished. Spit heartily in her drink when she goes to the dance floor. Spit and liquor swirling in foamy white loops. Swirling, honey pie, like piss down the drain.

Next there are eyewitness reports. Sightings: Barton, Benton. He will pound his fist onto the kitchen countertop, phone pressed wet to his face. A gust of hot wind blows into your eyes and your nose spasms.

This is no time for miracles.

There will be police interviews, statements and co-signatures. There will be nothing for you to do. He has already posted signs everywhere conceivable: on desktops, over freeways, over other signs. Someone will call from the police station: relatives’ names, phone numbers, addresses needed. Ask where his parents live nowadays and he’ll just go grinning from ear to ear. Smile back. He will laugh at something, hours later, completely unrelated. But wheezing. Rioting. Roaring at the television screen in the next room. Bolt in and ask him what’s wrong. Roll together on the floor in front of the TV stand. Afterward, there is nothing else to be done. Afterward, he will dangle half off the rug, completely used.

Continue to pace. Despite fake New Jersey accent, feel unamused by his antics. Look at your wrinkly knuckles. If ever you would leave him. Glance at your cell phone. It wouldn’t be in spring.

There is never any news, just a telephone rocking endlessly in its cradle.

Once a week you will bring up her name in casual conversation, in public. Manage expectations. Tell the old ladies huddled around you that the police have made no promises. “We do what we can,” you tell them, never looking away from the tight, anxious circle, never quite meeting his eyes.

The thought will occur to you that you are waiting for her permission to flee.

You will pass your father on the street, or maybe back at the hardware store. Begin by calling him “Pa”. Begin by asking what he’s been up to lately and walking him back to his house. Meet his wife. She will talk in a thick, European accent. She will respect only the working man, eat very little, eat only on divinely immaculate plates. End it the second time he shouts at you to get the hell out.

There is never any news, just a telephone wailing endlessly for its mother.

Fantasize about a dead body. It is a study in exhaustion, an examination of the end of the rope. You would be comforted by his bony sister and his sobbing ex-girlfriend. The three of you in the depths of the morgue would hurl yourselves at the steel table, then surge backwards. You, especially, would kick your feet, stumble and howl, bare your wrists. Your mother would be proud

After dinners with your father: slink home. Your breasts will ache, your knees will lock. Neighbors will be rocking on their front porches, staring over you as you cringe past. You recall. Remember: nine years ago, a night like any other night in January, your mother already three hundred miles away in a scrubbed clean Chevy, your father stalking through the deserted streets, you following after like a famine. Damn it, he bellowed, god damn it, Lorraine! Lights snapped on in houses, then blinked out with swift apologizes. The two of you were the spooks haunting the streets that night. Lorraine. Mama. Lorraine. It ran cracks through the midnight stillness. Lorraine.

If you could only love one woman in your life you would choose your mother. If you were being introspective, you’d say it’s because she was gone after you were six years old, but you’re not like that. You are a runner and a bailer and a grudge-holder and a tongue-holder. You ignore him studiously, lying next to you in bed calling you baby. Calling to you. “Baby, we have to figure this out. I can’t lose you again. Baby?” You spend the nights under his heavy, stuffed quilt playing out fantasies, that your mother spent five years in Africa before settling in Queens. She called you one morning: Heard you got out too. How’d it go?

Recently she’s gone on these little pink pills that make her consider her shrink her best friend and watch movies only to pre-curse a tearful rehash of her childhood, but god dammit, if she’s not going to act like your mother than you will.

Roll over to face him, but don’t move an inch closer. Don’t tell him any of this, anything. Instead: promises. Promises out the wazoo.

Slink. It won’t matter. Your ex-husband will be pacing the living room looking fearsome. He will slap you, bite you, taste you. Kiss him, soothe him. Make love to him without batting an eyelash. Splash water on your face in the bathroom at four in the morning. Nothing will matter.

Make him breakfast. Your ex-husband will ask quietly about your work. Lie. Tell him you build model boats for tourists. Smoothed, streamlined little things. He will ask about selling, marketing rights, inflation. Lie, always. Tell him, no, oh no, you aren’t involved in any of that. You have a friend in Seattle who takes care of it. You just build them, beautiful little boats. He will not eat your French toast. He will stir it on his plate with the butt end of his fork, and then hurl it against the wall.

At night you will be anxious for the weather to warm. You will pace the front porch like you are waiting for a package, for justice, for sunrise. He will not wait up for you.

When you go out, leave him a list of groceries that need purchasing, dry cleaning that requires his attention. Wait outside. Lie beside the porch and watch the clear sky darken. You could lie there until the end of time. When he lumbers to his car, count to sixty before getting up. Go back inside. Go to stand in front of the wide kitchen windows. Stand stalk still. Watch cars and bicyclists zip past. Lie, when he comes home again. Tell him you wanted to go visit your father for once, just to see how he’d been. No one was home.

There is never any news, just the phone sucking absently on its toe.

This is how you go.

Flossing and primping in the early morning, with the bathroom door open, staring at his shape on the bed in the bedroom.

Peanuts and a 7-Up. Leaning your seat back almost into someone else’s lap.

You will never see him again. Or maybe you will, whatever. But her you’ll see daily. Her picture you put on your refrigerator, above your mantle, clamped in a locket. It becomes a conversation piece. When men come over, they ask questions. You tell them you named her Agatha, after your grandmother, after your best friend in college.

The phone will roll and roll in its cradle.

Four years, one month, three weeks, and so much more. They found her bones buried three miles outside of town. Call your mother back. The sun rises outside your window, out on the curb. The fog rolls in, but it dissipates. One of those mornings.